What’s on the line with Tuesday’s CPI figures?

While much of Wall Street anticipates a softening in inflation, an unexpected surge could quash hopes for a May rate adjustment, potentially putting a damper on the S&P 500’s march towards 5,000, caution some analysts.

However, in the midst of Nvidia’s remarkable 47% surge this year and the AI frenzy propelling companies like ARM, it seems prudent to avoid standing in the way of tech-driven momentum, at least for now. Indeed, Bank of America’s recent survey of fund managers indicates unabated enthusiasm for tech stocks.

So, what might eventually trigger a downturn in this market? According to former hedge-fund manager Russell Clark, attention should turn to Japan, where loose monetary policy persists as a last bastion.

Clark, despite exiting his perennially bearish RC Global Fund in 2021 after a decade of misjudgments on stock markets, puts forth a compelling theory on Japan’s significance.

In his Substack post, Clark contends that the true catalyst for a bear market will arise when the Bank of Japan terminates quantitative easing. He argues that we inhabit a “pro-labor world,” where certain dynamics should be unfolding: rising wages, diminishing unemployment, and interest rates trending higher than expected. Aligning with his projections, real assets began a surge in late 2023 coinciding with the Fed’s dovish stance and a steepening yield curve.

However, subsequent events haven’t neatly matched his expectations. While he anticipated that higher short-term rates would drain speculative asset investments, money instead flowed into cryptocurrencies like Tether, and the Nasdaq rebounded entirely from its 2022 downturn.

Returning to Japan, Clark provides a less conventional explanation for why financial and speculative assets continue to perform strongly.

He observes that during the 1990s, despite the Fed maintaining high interest rates, the dot-com bubble flourished. However, the bubble eventually burst when the Bank of Japan finally raised rates in 1999. Similarly, Japan’s attempt to raise rates in 1996 is associated with the Asian Financial Crisis.

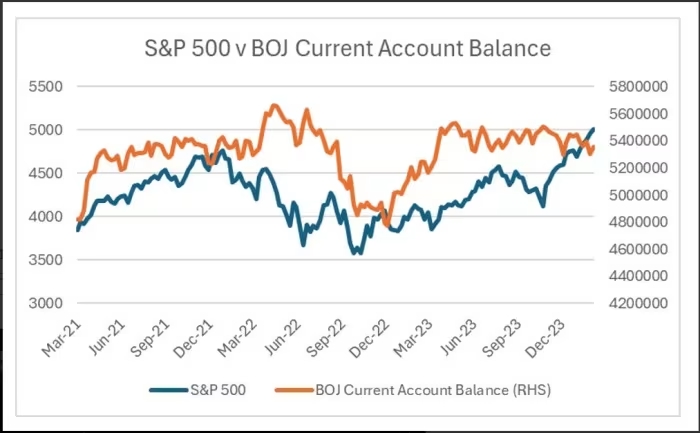

In Clark’s analysis, it appears that markets are more attuned to the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet than the Fed’s policies. He argues that the BOJ’s introduction of quantitative easing in the early 2000s preceded the subprime crisis, which erupted shortly after the BOJ withdrew liquidity from the market in 2006.

According to Clark, this correlation also explains why rising bond yields haven’t significantly impacted assets. As Japanese government bond yields have climbed, the BOJ has committed to unlimited purchases to keep them below 1%.

The key takeaways? “BOJ is the only central bank that matters… and that we need to adopt a bearish stance on the U.S. when the BOJ raises interest rates,” asserts Clark, who views a bear market as advantageous for his plans for a new fund. He closely monitors the BOJ’s actions as a harbinger of market shifts.