Who Controls the 10-Year Yield? The Market Holds the Reins

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell may be breathing a sigh of relief as the Trump administration shifts its focus to the 10-year Treasury yield rather than pressuring the Fed for rate cuts. However, this pivot raises new concerns among market participants.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent clarified the administration’s stance in recent interviews with Fox Business Network’s “Kudlow” and Bloomberg Television. He emphasized that President Trump is not advocating for immediate rate cuts but instead expects the 10-year yield to decline naturally due to policy measures.

Bessent’s comments temporarily eased concerns about potential White House interference with Fed policy. Just weeks earlier, Trump’s demand for immediate rate cuts had amplified worries about his approach to central bank independence. However, the shift in focus to the 10-year yield presents fresh challenges, including the inflationary effects of tariffs and the U.S.’s mounting $2 trillion budget deficit, which could necessitate even greater Treasury issuance in the years ahead.

Mark Malek, chief investment officer at Siebert, highlighted a fundamental truth: “Who is in control of 10-year yields? The answer is quite simple: THE MARKET.” Malek pointed to rising inflation expectations, trade tensions, and deficit-driven debt issuance as key drivers of recent yield increases.

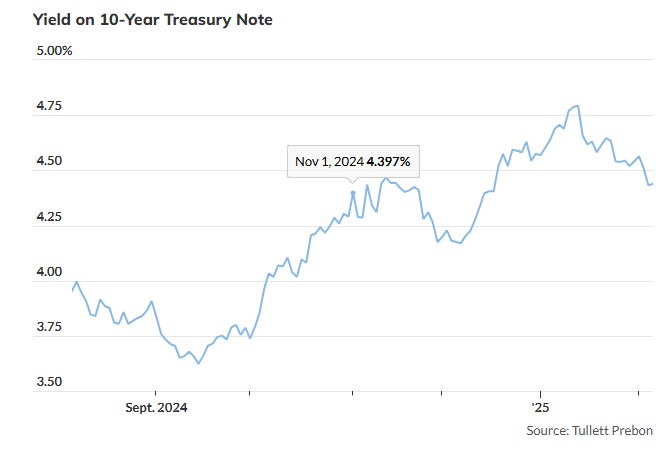

Over the past few months, the benchmark 10-year yield—crucial for borrowing costs on mortgages, car loans, and student loans—has surged more than a percentage point, peaking at 4.802% on January 13 from 3.622% on September 16. However, following Trump’s announcement of tariffs on Mexico and Canada, then his subsequent decision to delay them, the yield settled just under 4.44% on Thursday.

While the administration could theoretically drive yields lower by influencing the Fed to purchase 10-year Treasurys—an approach known as yield-curve management—Malek views this as unlikely. Historically, the U.S. deployed yield-curve control during and after World War II to manage war debt, and Japan has more recently employed similar strategies.

Alternatively, the Treasury Department could consider a buyback of long-term Treasurys, financing the purchase through short-term debt issuance, mimicking the Fed’s 2012 Operation Twist program. However, market reaction to such measures remains uncertain.

Despite Bessent’s remarks, yields on 2-, 10-, and 30-year Treasurys edged higher on Thursday, suggesting limited immediate impact. Meanwhile, stock indices ended mixed, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average, S&P 500, and Nasdaq showing slight declines.

Gregory Faranello, head of U.S. rates trading and strategy at AmeriVet Securities, acknowledged the administration’s reasoning but underscored the challenges ahead. “In a nutshell, it’s hard to have your cake and eat it too,” he said. While markets respond positively to softened tariff policies, structural issues such as above-trend economic growth (2% to 2.5%) and inflation (2.5% to 3%) pose barriers to significantly lower rates.

Faranello argued that the key to reducing rates lies in addressing energy prices, economic policy, and supply chain dynamics. He also noted that sustained Treasury issuance to finance government operations complicates efforts to drive yields lower. While an Operation Twist-style program remains an option, he questioned its effectiveness, emphasizing that inflation remains the dominant factor influencing interest rates.

As the administration refines its approach, one reality remains unchanged: The market dictates the direction of 10-year yields, not policymakers.